The first week of the Old Vic in Sydney, 1948

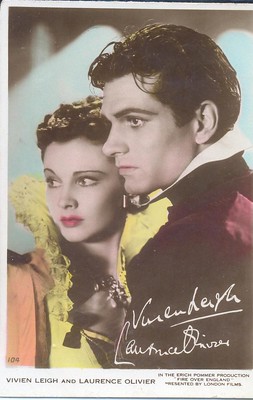

The Old Vic tour of 1948 lingered long in the memories of Sydneysiders. The tour was notable for the stars, Sir Laurence and Lady Olivier, also known as Vivien Leigh. The man in the bookstore was one of many whose life was touched by contact with the magical pair.

On June 20th 1948, Sir Laurence Olivier and his wife Vivien Leigh, had their first glimpse of Sydney. The Sydney Morning Herald memorialised this important event the next day. The couple were just passing through the city, yet the occasion was so momentous, it was front page news. Amidst the stories of murder, the red menace and continued turmoil in Germany was a picture of the Oliviers. Vivien’s, Scarlett smile was the dominant feature of the photograph. Three hundred people had gathered to greet the pair as they spent twenty minutes at the airport on their way to Brisbane. Vivien had time to compliment Australia.

The people have given us a splendid reception

Sir Laurence added

We are both exhausted after a busy time in Melbourne and Tasmania.

Then they continued their journey.

The next day the couple was front page news again. Nestled beneath the news that clothing and meat rationing had ended, was the headline. "Oliviers quit hotel to escape curious crowd." The pair had been forced to leave their Queensland hotel due to a large number of people trying to see them. Olivier, obviously desperate for some privacy, had told photographers,

We came here for privacy and we are entitled to it. When we are on the job

we put everything we have into it and we want to relax completely now.

The couple soon moved to a more private location. The Sydney Morning Herald was quick to inform its readers that their new home was furnished but had no linen. By this time, no detail was too trivial for the newspapers.

Finally after a week in Queensland the couple returned to Sydney. On Sunday June 27th they moved to a flat in Cremorne. Yet defeated by gas and electricity rationing caused by industrial unrest on the coalfields, they soon decamped to the Hotel Australia.

On Monday 28th June , their arrival made front page news again. "Oliviers here, (not yet in limelight)" was the Sydney Morning Herald headline.

On June 29th the paper published some public comments by Sir Laurence. He was obviously ‘on the job’ and made some remarkable statements about theatre in Australia.

Sir Laurence said that Australia could not expect to build a theatrical

tradition while it permitted its best actors to go overseas.

He then discussed the idea of having a national theatre in Australia.

A national theatre will give you fine theatre buildings, but not actors. They are

best developed by establishing theatre schools.

Olivier took his position as a knight of the theatre very seriously. He promoted theatre whilst in Australia and he and Vivien visited local productions. They saw a production by the Independent theatre and met Doris Fitton. They also viewed a performance by Peter Finch . Despite his insistence that Australia needed to keep her native actors, Olivier was not above luring Finch to England with the promise of a contract.

During this interview Olivier again emphasised the fact that he and Lady Olivier were exhausted. It was an attempt to escape the large number of social invitations the couple received.

In Melbourne, I was absent from the theatre because of illness for three nights, and my wife

for seven nights. It was a shocking state of affairs and must not happen again.

Sir Laurence was quoted extensively throughout the couple’s stay in Sydney. Vivien, probably more famous because of her film roles, was not prominent in these articles. The press were acknowledging Olivier’s role as the head of the Old Vic and reinforcing his traditional male role as head of the household.

The Old Vic opened their season with a performance of The School forScandal at Sydney’s Tivoli Theatre on June 29th 1948. It was a gala occasion. The most well dressed first night crowd since 1939 attended. Women wore magnificent furs and hyacinths, roses and orchids decorated their elaborate evening gowns. Miss Jocelyn Rickard covered her shoulders with a beaded and sequined net shawl that shimmered as she walked.

The men were also dressed for the occasion. Mr John Bovill caused a sensation with his fur collared evening cloak. Three gentlemen wore top hats, an unusual accessory. They doffed the hats in courtly greeting as friends passed by.

Luminaries such as Chips Rafferty, Governor General McKell and the Sydney Lord Mayor attended. The excitement was so intense that the spectacular crowd was reluctant to leave the theatre entrance.

After the performance, a select group of fifty people were invited to meet Sir Laurence and Lady Olivier in the dress circle foyer. A picture of a beaming Vivien dressed in a light coloured frock, with a darkly garbed Olivier looming behind her, graced the pages of the Sydney Morning Herald.

The next day the couple attended a reception at the Sydney Town Hall. It was an indication that Sir Laurence and Lady Olivier were more than mere actors. They were ambassadors for England, representatives of the Old Vic, acting theorists, film stars and theatre actors. Their varied roles were illustrated by the variety of events they attended in Sydney. Sir Laurence gave a lecture at Sydney University, Vivien opened a flower show, they recorded their performances for ABC radio, they organised entertainment for the rest of the company, and they gave over sixty performances in the space of two months. It was a hectic, stressful and taxing tour for both of them.

One of the expected highlights of the tour was Olivier’s performance of Richard the Third. It was one of his most famous roles and highly anticipated in Sydney. Olivier had first played the Yorkist king in 1944. The performance had been hailed by critics as one of his greatest. Olivier based the character in part on real people, Hitler being one of them. The actor placed great emphasis on assembling the character from the outside in. He was particular about the external features and with Richard this was exemplified by the prominent false nose.

The first night of Richard III in Sydney was July 2nd. It was a more subdued event than the earlier opening of School for Scandal. The ladies wore long flowing gowns, orchids and fur coats. Yet the gentlemen had left the top hats at home. There were several family parties, the parents being anxious to introduce their children to Shakespeare. There was also a group of uniformed schoolgirls from Sydney Church of England Grammar School. It was an audience that was seeking an education rather than glamour.

Olivier’s Richard dominated the play from beginning to end. He played the king with a nasal tinge to his voice, a pendulous upper lip curled in a permanent snarl, a limp, and a withered arm, that he tried desperately to conceal. According to the Sydney Morning Herald critic, Olivier’s Richard sought power to compensate for his physical deformities. Olivier also played Richard as a man who saw murder as a joke. This interpretation caused some consternation. The reviewer thought that Olivier carried the flippancy a little too far. However, the review also acknowledged the superb achievement and power of Olivier’s performance. His charisma over the footlights must have been immense and awe inspiring. The audience was impressed. The play received a huge ovation from a very enthusiastic crowd.

Olivier made a brief speech after the sixth curtain call.

The body of Richard when it was taken from Bosworth field was so mangled

so as to be unrecognisable and it was finally thrown onto an ox cart. So you can

see that he was in no position or situation to make speeches. He and his author rise

from their graves to say thank you for your reception.

At the matinee the next day, Olivier injured his knee during the climactic battle scene. He continued the show regardless. On Monday night he incorporated a wooden T-shaped crutch into the performance. According to the Sydney Morning Herald, this addition altered the character of Richard greatly. Instead of the virile and active king of the first night, he became a twisted, bitter man who hated his infirmity. It was an accident that improved the performance. Olivier’s ability to innovate placed him in the realm of the great. His intimacy with the character allowed him to incorporate elements of his own personality and life into the fictional recreation.

On Tuesday July 6th, the Old Vic presented the third play in its repertoire. Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of our Teeth. The play was a wild, zany romp through the history of mankind. It showcased Vivien as Sabina and she rose magnificently to the occasion.

As chambermaid or beauty queen she is the perpetual minx of history who back answers

or seduces in tones that are the distillation of applesauce.

The Sydney Morning Herald reviewer called it, ‘beautifully pointed acting.’

The general tone of the reviews was one of respect mingled with mild criticism. It was obvious that Sydney reviewers held Sir Laurence and Lady Olivier in awe, but the other members of the cast were considered disappointing. The Sydney Morning Herald thought that the supporting cast of Richard was lacking and suggested that they needed to loosen up for The Skin of our Teeth. Both Oliviers escaped major criticism. Their names alone ensured a sell out season at the Tivoli. To many Australians seeing the Oliviers either on stage or meeting them in person was a lifelong highlight. The glittering couple were the personification of wealth, fame and happiness . There was an aura of charisma and charm surrounding them. They caused excitement through Sydney and ensured that people began to speak of ‘the theatre’ again. Olivier’s comments on a national theatre caused a small ripple of discussion in theatrical circles. A ripple that took a decade to become a wave. The ability of the pair to maintain a polite and friendly facade despite the stresses of the tour was remarkable. Their visit to these shores will always be fondly remembered

.jpg)